Page 2 of 4

PROFESSIONAL SEMINAR SERIES

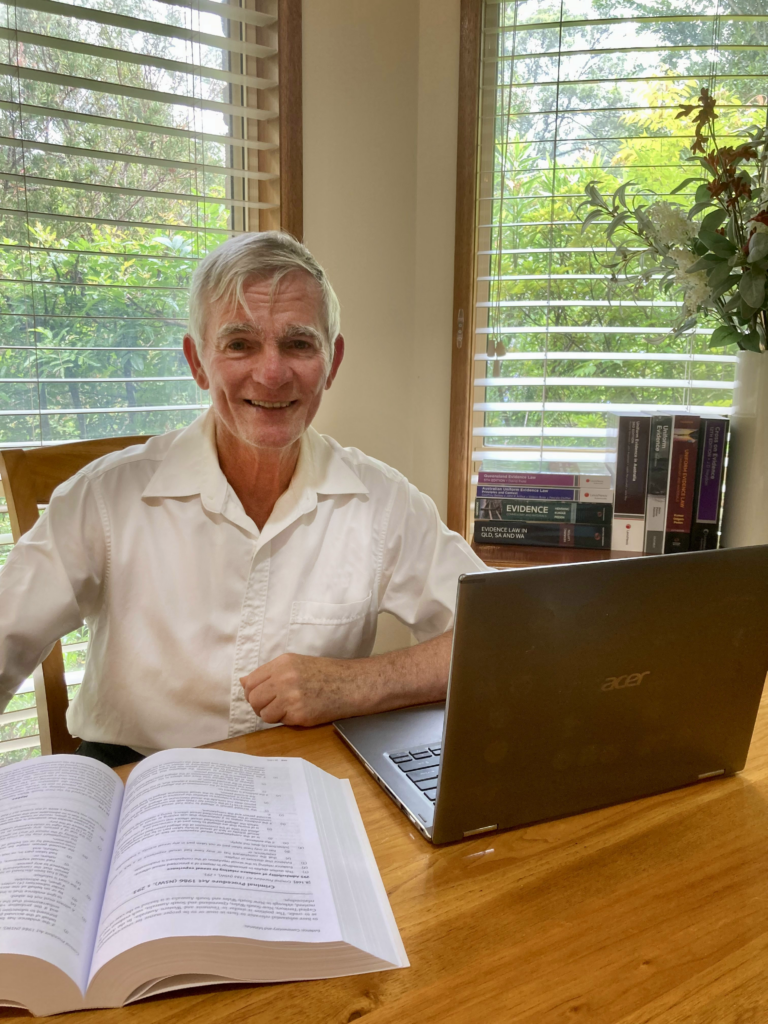

Dr Timothy Nugent

Deus Ex Machina: Exploring Implications of Generative AI for Lawyers

3 December 2024

5:30pm-6:30pm

Nibbles to follow

UniSQ Toowoomba

Room Q402,

487-535 West St,

Darling Heights

Pricing

Member & Student: $15.00

Non-Member: $25.00

Beyond ‘Adult Time, Adult Crime’: The Reality of Queensland’s Youth Justice Act in a New Political Era

This post is the second academic post examining Queensland’s Liberal National Party’s ‘adult crime, adult time’ policy. The posts are designed to ignite thoughtful discussion and debate. Mrs Kirstie Smith now offers her response to Associate Professor Andrew Hemming’s provocative analysis.

By Mrs Kirstie Smith, University of Southern Queensland

Introduction

As Queensland enters a new political era following this weekend’s election, it’s crucial to examine claims that have shaped the youth justice debate. The campaign’s central premise rested on the proposition that criminal offending results from rational choice and can be deterred through punishment. Moreover, Associate Professor Andrew Hemming’s recent assertion that the current system operates merely as a ‘get out of jail free card’ for Queensland youth, coupled with claims of ‘weak’ judicial decision-making ‘hampered’ by restrictive laws, demands careful scrutiny. These arguments, while politically potent, overlook Queensland’s growing body of mandatory sentencing orders and the crucial role of judicial discretion in achieving just outcomes.

Sentencing: Beyond the ‘Feel Good’ Response

The act of sentencing is a sophisticated balance of legislative purpose, legal principles, mitigation features, and circumstances of aggravation. These are predominantly set out in the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld) and work in conjunction with the Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld). While historically a key sentencing principle held that imprisonment should only be imposed as a last resort, this principle exists alongside deterrence objectives. As Justice Spigelman astutely observed:

The ineluctable core of the sentencing task is a process of balancing overlapping contradictory and incommensurable objectives. The requirements of deterrence, rehabilitation, denunciation, punishment, and restorative justice do not generally point in the same direction. Specifically, the requirements of justice, in the sense of just deserts, and of mercy, often conflict.

Legislative Changes and Their Impact

Associate Professor Hemming’s critique of child offender identity protection, particularly in the context of social media boasting, raises superficially compelling arguments. However, this perspective overlooks the substantial legislative response already enacted. Queensland governments have amended the Youth Justice Act over ten times in the last decade, including significant changes through the Strengthening Community Safety Act 2024 (Qld).

A key change has been the amendment of Principle 18, which previously enshrined detention as a last resort, stating that a ‘child should be detained in custody for an offence, whether on arrest, remand or sentence, only as a last resort and for the least time that is justified in the circumstances.’ The removal of ‘last resort’ fundamentally alters how courts approach youth detention, shifting from a presumption against custody to a more open-ended assessment of what time is ‘justified in the circumstances.’

The statute also modified the Childrens Court Act 1992 (Qld) to create a presumption of open proceedings for victims, relatives of deceased victims, and accredited media. Now, interested parties must be specifically excluded on a case-by-case basis. This operates alongside new offences criminalising the publication of criminal activity on social media, with heightened penalties where motor vehicles are involved. In addition, the penalties for unlawful use of motor vehicles were increased for both adults and children, with additional increases for the theft of vehicles at night. The Labour government had also introduced ‘extreme high visibility police patrols’ to deter would-be criminals from offending in the first place.

Case Study: The Limits of Deterrence in Knife Crime

Queensland’s approach to knife crime provides an excellent contemporary case study through which to examine both the deterrent effects of legislative change and the impact of public sentiment on maintaining punitive penalties. Recent tragic events — including the stabbing death of grandmother Vyleen White, the Bondi Junction attacks, and the stabbing of Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel — have intensified focus on both penalties and police ‘stop and search’ powers. However, this reactive pattern of legislative response to public fear has a longer history.

In 2005, Bondy, Ogilvie and Astbury examined the rationale for expanding weapon control legislation. They cited the Law Reform Commission of Victoria’s caution that being armed with an offensive weapon ‘cannot be expected to have any impact on these types of serious, premeditated crime,’ emphasising that increased legislative controls should only be introduced when a ‘clear and demonstrable need exists.’ Despite this, legislative expansion typically followed high-profile incidents, with their research finding that traditional enforcement approaches only ‘played a subsidiary role in reducing young people’s weapon possession and carriage.’

The Australian Institute of Criminology’s 2011 report reinforced these findings, citing evidence from the UK that tougher penalties neither deterred knife carrying nor reduced reoffending; in fact, imprisonment increased recidivism. If deterrence worked as claimed, increased penalties should have shown immediate correlative effects. Instead, Parliament noted an 18% increase in knife-related offences from 2019 to 2023, despite implementing extensive ‘safe spaces’ trials, public campaigns, and restrictions on knife sales to minors.

Yet this evidence hasn’t deterred Premier Crisafulli from advocating, or former Premier Miles from expanding, existing legislation, police powers, and education regimes, including a $6 million boost to knife crime prevention campaigns announced in February 2024. This phenomenon can be understood as ‘cathartic’ — the public, largely unaffected by these selective restrictions, feels reassured that their fears have been recognised and something has been done, regardless of whether the measures are justified by evidence.

The Reality of Youth Crime Statistics

Fear and distrust have become the default safety measures in what media outlets portray as an era of unprecedented youth crime. Following election promises, late-night news broadcasts, and talk-back radio rhetoric, one might believe owning a car in Queensland has become an act of reckless optimism, given the supposedly inevitable theft by ‘untouchable’ young offenders. This narrative, however compelling for headlines and political campaigns, crumbles under the weight of empirical evidence and comes with a costly price tag.

The 2024–25 Budget allocates $365.1 million over four years to Youth Justice as part of a $1.28 billion Community Safety Plan. Of this, $224.2 million is earmarked for youth detention infrastructure, including the Woodford Youth Detention Centre, while $94 million will operate the Wacol Youth Remand Centre. Yet the Queensland Audit Office‘s 2024 report reveals youth crime has been steadily decreasing for over a decade. The number of young people charged with offences has fallen from 14,485 in 2011–12 to 10,304 in 2021–22. Perhaps more tellingly, youth offenders’ contribution to overall crime has decreased from 17% in 2011–12 to just 13% in 2022–23.

Queensland Youth Crime Trends

| Year | Young Offenders | % of Total Crime |

|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | 14,485 | 17% |

| 2021–22 | 10,304 | 13% |

| 2022–23 | 10,878 | 13% |

Youth Justice Budget Allocation 2024–25

| Category | Amount (millions) |

|---|---|

| Detention Infrastructure | $224.2 |

| Wacol Youth Remand Centre | $94.0 |

| Other Programs & Services | $46.9 |

| Total | $365.1 |

This statistical reality raises serious questions about the allocation of public resources. While $221.1 million is dedicated to detention infrastructure in 2024–25 alone, community-based orders — which show success rates of 87% for non-Indigenous youth and 77% for Indigenous youth — receive comparatively modest investment.

What we are witnessing is not a crime wave but rather a surge in alarmist and misleading headlines designed to instil fear, increase clicks, and sell subscriptions. Historical analysis by ABC News reveals this is not a new phenomenon: Queensland’s media has consistently blamed ‘crime waves’ on ‘spoilt children, irresponsible parents, and lenient judges’ since the 1800s, regardless of actual crime rates. Neither mainstream media outlets nor the state’s politicians appear interested in presenting these statistical realities. Instead, nuanced discussion of underlying issues remains notably absent while rhetorical attacks on the judiciary and political opponents continue, threatening to destabilise trust in democratic institutions and blur the separation of powers.

The new budget does include some promising initiatives, such as the Intensive On Country Program for Indigenous youth and expanded after-hours services, but these remain overshadowed by the emphasis on detention infrastructure.

This disconnect between public perception and statistical reality creates a challenging environment for evidence-based policy making. When fear drives policy, we risk implementing ineffective but politically expedient solutions while overlooking proven interventions that could genuinely reduce youth offending. We also further cripple the human rights not only of our most vulnerable, Queensland’s children, but of everyone. These legislative amendments and presumptive onus shifts apply to all — a fact that escapes most until it applies to them.

Moving Forward: The Challenge of Evidence-Based Reform

As Queensland enters this new political era, the challenge lies in reconciling ‘Adult Crime, Adult Time’ rhetoric with evidence-based approaches. While increased penalties may satisfy public demand for action, we know that short sentences of imprisonment provide no beneficial outcomes despite satisfying the ‘principle of deterrence’ (R v Hamstra [2020] QCA 185).

The reality of Queensland’s youth justice system is far more nuanced than recent political discourse suggests. While Dr Hemming’s critiques and the new government’s ‘Adult Crime, Adult Time’ policy may resonate with public sentiment, they overlook both the substantial existing framework of penalties and the empirical evidence about youth crime trends and effective interventions. Moving forward, the focus must remain on evidence-based approaches to reducing youth offending rather than politically expedient solutions if we really want to act ‘in victim’s best interests’.

Author

Kirstie Smith is a Mununjali, Yugembeh woman and Lecturer in Law at the University of Southern Queensland, based at the Toowoomba campus on Jagera, Giabal and Jarowair country. She practises in criminal defence in Toowoomba.

Kirstie serves on the executive committees of both the Downs and South West Queensland Law Association and the Queensland Law Society’s Future Leaders Committee. She is an active member of Women Lawyers Association Queensland, Australian Lawyers for Human Rights Inc, and Indigenous Lawyers Association Queensland.

This post is the first in a series of academic posts examining Queensland’s Liberal National Party’s ‘adult crime, adult time’ policy. The posts are designed to ignite thoughtful discussion and debate. Associate Professor Andrew Hemming begins the conversation with a provocative analysis, with Mrs Kirstie Smith set to offer her response in the following post.

By Associate Professor Andrew Hemming, University of Southern Queensland

Introduction: A Policy That Doesn’t Go Far Enough

David Crisafulli’s announcement of the Queensland Liberal National Party’s ‘adult crime, adult time’ policy to combat youth crime has one major limitation: it does not go far enough. The stumbling block is the misleadingly entitled Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld) which is essentially a ‘get out of jail free card’ to Queensland’s youth. The legislation is based on the outdated neuroscience that juvenile offenders should face lesser sentences than adults because they are liable to make irrational decisions on account of peer pressure and emotional immaturity causing them to engage in high-risk behaviour.

Outdated Neuroscience: A Flawed Foundation for Youth Sentencing

The most recent neuroscience (2022) emanating from the United States is focused on the teenage brain. The old assumption that adolescents were risk machines lacking the decision-making powers of a fully developed prefrontal cortex is being challenged:

There is growing recognition that what was previously seen as immaturity is actually a cognitive, behavioral, and neurological flexibility that allows teens to explore and adapt to their shifting inner and outer worlds.

Zara Abrams, ‘What neuroscience tells us about the teenage brain’ (2022) 53(5) American Psychological Association 66.

This means that neuroscientists are now not viewing the developing brain as broken, immature or contributing to problematic behaviour, but rather as ‘malleable, flexible and promoting many positive aspects of development in adolescence’ (ibid, Abrams).

The Inadequacies of the Youth Justice Act: Protecting Offenders, Not Victims

The inadequacies of the Youth Justice Act are fundamental, commencing with the definition of a child as a person under 18 years of age. As a society, we are prepared to allow a young person to be in unsupervised control of a motor vehicle, a potentially lethal weapon, at 17 years of age, but are content to leave the age of adult criminal responsibility at 18 years of age. Why?

Perversely, under the Youth Justice Act young offenders cannot be identified, yet many seek celebrity status by boasting and posting videos on social media about their successes in stealing cars, destroying other people’s property and the like. Why should the identity of such blatant amoral publicity seekers be protected?

Case Studies: The Price of Leniency

David Crisafulli declared that the soft policing of teenagers and a dearth of serious consequences after committing serious crimes had created ‘a generation of untouchables’. Crisafulli is correct in his assertion. For example, under s 183(1) of the Youth Justice Act the default position is that ‘a conviction is not to be recorded against a child who is found guilty of an offence’. Under limited circumstances, a conviction may be recorded at the discretion of the court.

Similarly, under s 155 of the Youth Justice Act, mandatory sentence provisions in any other Queensland legislation are inapplicable and the court must disregard them. If an adult is found guilty of murder, under s 305 of the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld), the mandatory sentence is imprisonment for life with a non-parole period of 20 years. However, if a 17-year-old is convicted of murder, s 155 of the Youth Justice Act requires the court to disregard s 305 of the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld). In its place, s 176(3)(a) of the Youth Justice Act sets out the default position for a life offence of a period of imprisonment of not more than 10 years. Only if the court considers the offence ‘to be a particularly heinous offence having regard to all the circumstances’ may the court sentence a ‘child’ murderer to more than 10 years imprisonment. The teenager aged 17 years and 8 months when he murdered Emma Lovell was found by the court to have committed a particularly heinous offence and was given a head sentence of 14 years imprisonment but is only required to serve 70 per cent of that in custody and will be released in 2032.

A further high-profile example of the leniency of the court when sentencing two juvenile offenders under the Youth Justice Act can be seen in the violent knife attack on former rugby union great Toutai Kefu and his family in their Brisbane home in 2021. Before breaking into the Kefu home, one of the boys remarked: ‘If someone wakes up, just stab them’. Despite the judge finding the stabbing attack was particularly heinous, the two offenders were sentenced in June by Justice Peter Davis to seven and eight years respectively, but due to ‘special circumstances’ are only required to serve 50% of their sentences. To boot neither had a conviction recorded. Unsurprisingly, the Queensland Attorney-General Yvette D’Ath has lodged an appeal over the sentences on the ground they are manifestly inadequate, especially given the finding the offences were particularly heinous and in light of the maximum possible life penalty.

Critics of the ‘Adult Crime, Adult Time’ Policy: Missing the Mark?

After Crisafulli announced his ‘adult crime, adult time’ policy, the media gave prominence to the predictable chorus of disapproval from the usual sources. Queensland Council for Civil Liberties vice president Terry O’Gorman attacked the policy because the necessary supporting policy work had not been completed:

Law and Order slogans are one thing. Doing the hard work to fix Queensland’s juvenile justice system is quite another.

In the same vein, Queensland Law Society president Rebecca Fogerty said the policy would do little to address the systemic issues at the root of youth crime offending:

Calling for longer sentences in a struggling detention system will not fix the problem of youth crime. It will need to more overcrowding, more violence, more lockdowns, less education and less rehabilitation. This will compound the issues we know give rise to serious repeat offending.

Of course, in the eyes of such critics the blame is never to be attached to the individual violent youths involved in these serious offences, but on their disadvantaged backgrounds and their experience of domestic violence. Therefore, the proposed solution is always allegedly to be found in vast public expenditure on social housing, better schools, more welfare support systems and a myriad of programs all to be paid for by the long-suffering taxpayer.

It is unrealistic and disingenuous to pretend such massive public expenditure will ever eventuate and the community has lost patience with the endless revolving door policy of serial youth offenders. As the then Queensland Attorney-General, Shannon Fentiman observed in 2021:

We know that 46 per cent of youth crime is committed by a small group of recidivist offenders.

Ironically, existing Queensland government policies, such as school exclusions, are contributing to the problem. There is a documented progression whereby short informal exclusions develop into longer, formal suspensions because exclusionary school discipline does not address the wider factors underlying the anti-social behaviour of children and can reinforce such behaviour (Inquiry into Suspension, Exclusion and Expulsion Processes in South Australian Government Schools, Final Report, The Centre for Inclusive Education, 26 October 2020). Exclusionary school discipline contributes to the ‘school-to-prison pipeline’.

Conclusion: Repealing the Youth Justice Act—A Necessary Step

Any proper risk analysis points to one sensible conclusion: the need to take such violent offenders out of circulation in the community for which they clearly have no respect. The alleged outcomes outlined by Fogerty will not eventuate if suitable additional youth detention centres are built, which does represent expenditure the community will support. Belatedly, the Queensland government has recognised this reality by finally committing to build two new youth detention centres in Woodford and Cairns, while also constructing the Wacol Youth Remand Centre which is scheduled to open at the end of 2024.

In sum, the Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld) needs to be repealed and more appropriate legislation introduced. Youth justice does not equal victim justice under the current Youth Justice Act.

Author

Andrew Hemming is an Associate Professor in Law at the University of Southern Queensland, based at the Toowoomba campus. A seasoned teacher and prolific author, he specialises in evidence and criminal law.

Andrew is known for his rigorous scholarship and passion for engaging in robust debate.

Introduction

The School of Law and Justice at UniSQ is excited to announce a new collaboration with the Downs and South West Queensland Law Association (DSWQLA). This partnership will deliver a series of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) seminars for legal professionals, law students, and academics. Our goal is to provide affordable and relevant CPD opportunities for regional lawyers. This will enhance their professional growth and foster a vibrant legal community.

Bridging the Gap for Regional Lawyers

Accessing quality CPD can be challenging for legal practitioners in regional areas due to geographical and financial constraints. Our partnership with DSWQLA aims to address these barriers. We offer in-person seminars at a reasonable cost. This ensures regional lawyers have the same opportunities for professional development as their metropolitan counterparts. This initiative supports individual growth and strengthens the legal community.

Upcoming Seminar: Mental Health Defences in Criminal Law

We are excited to start our CPD series with a seminar on “Mental Health Defences in Criminal Law.” The seminar will be presented by Matthew Le Grand, Principal Crown Prosecutor at the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. This event promises invaluable insights into a critical aspect of criminal law. Attendees will gain knowledge and skills needed to navigate complex legal issues related to mental health and advocacy.

Event Details

- Date: 18 July 2024

- Time: 5:30pm

- Venue: Room B102, UniSQ, West St (see interactive Toowoomba campus map)

- Tickets: $25 for Members & Students, $30 for Non-Members

- Extras: Nibbles and drinks will be provided

Join Us for an Evening of Learning and Networking

We invite legal professionals, law students, and academics to join us for this informative seminar. Attendees will benefit from Matthew Le Grand’s expertise. Moreover, they will have the chance to network with peers and engage with the local legal community. This event is a great opportunity to expand your knowledge, connect with others in the field, and support the professional development of regional lawyers.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to Kirstie Smith for securing Matt as speaker for our inaugural seminar.

How to Purchase Tickets

Tickets can be purchased easily by scanning the QR code below (see promotional flyer) or by clicking here. Don’t miss out on this unique opportunity to enhance your professional skills and connect with the legal community.

Conclusion

The collaboration between UniSQ and DSWQLA marks a significant step forward. By participating in our CPD series, you are investing in your professional development. You are also contributing to the growth and vitality of our legal community. We look forward to seeing you at our upcoming seminar and many more to come.

Call to Action

Stay tuned for more updates on our CPD series and other exciting events. Follow the School of Law and Justice on LinkedIn or subscribe to the DSWQLA mailing list. Together, let’s continue to empower and support the legal professionals of our region.

#UniSQ #DSWQLA #LegalProfessionals #LawStudents #Academics #CPD #LegalEducation #Collaboration #ProfessionalDevelopment

By Dr Aaron Timoshanko, University of Southern Queensland

The legal profession is experiencing an unprecedented wave of change. From the COVID-19 pandemic to rapid technological advancements, lawyers and law firms are facing new challenges that demand innovative responses. A recent study published in the International Journal of the Legal Profession sheds light on how solo, micro, small, and medium-sized (SMSM) law firms in Queensland are adapting to these disruptions.

Key findings

The study highlighted several key findings that reveal how SMSM law firms in Queensland are responding to disruptions:

- Resilience in the face of change: Contrary to the stereotype of lawyers as technology laggards, the study found that Queensland’s SMSM firms demonstrated progressiveness and willingness to innovate. Most practices reported coping well during the COVID-19 pandemic, and respondents felt confident about handling future disruptions.

- Technology adoption: Most firms surveyed use cloud-based practice management software, which facilitated smooth transitions to remote work during lockdowns. Respondents generally held positive attitudes towards technology in legal practice, though some wariness remains.

- Barriers to practice: The study identified three key barriers affecting firms’ ability to address disruption: workload pressures, information overload, and tasks associated with operating a business. Notably, these barriers are more related to human capital than technological or disaster-related disruptions.

- Confidence in handling threats: Interestingly, respondents reported feeling more confident in addressing external threats (like cybersecurity attacks or economic downturns) than internal threats (such as the loss of key staff). This suggests a potential blind spot in business planning and succession strategies.

- Desire for trusted information: Practitioners expressed a strong desire for impartial information and training from trustworthy sources, particularly their professional associations, to help them navigate disruptions and adopt new technologies.

Implications for Queensland’s legal profession

These findings have significant implications for the future of the legal profession in Queensland:

- Enhanced role for professional associations: The Queensland Law Society and other professional bodies have a crucial role to play in providing trusted, impartial information and training to help firms adapt to disruption. This could include educational sessions on technological developments, best practices for selecting new platforms, and strategies for managing emerging threats.

- Focus on business planning: The finding that firms feel less confident handling internal threats highlights the need for greater emphasis on business planning, succession strategies, and risk management. Law societies could provide targeted resources and training in these areas.

- Time management as a critical skill: With workload pressures and information overload identified as major barriers, developing effective time management strategies becomes crucial. Firms may need to explore new technologies and processes to streamline administrative tasks and free up time for strategic planning.

- Cybersecurity awareness: While respondents reported confidence in handling cybersecurity threats, this may indicate overconfidence, given the sophistication of modern cyber-attacks. Increased education and resources on cybersecurity best practices should be a priority.

- Leveraging alternative business structures: The high proportion of incorporated legal practices (ILPs) among respondents suggests that firms are already adopting more flexible business models. This trend could be further encouraged to enhance firms’ adaptability and competitiveness.

- Balancing innovation and ethics: As firms adopt new technologies, including AI tools like ChatGPT, there’s a need for clear guidance on ethical use and best practices. Professional bodies and regulators should work proactively to address these emerging challenges.

The legal profession in Queensland, like elsewhere, is at a crossroads. While SMSM law firms have shown resilience and adaptability, they face significant challenges in navigating an increasingly complex and disruptive landscape.

By focusing on strategic planning, effectively leveraging technology, and tapping into the resources of professional associations, these firms can position themselves not just to survive but to thrive in the face of future disruptions. The key will be balancing innovation with the core ethical principles that have long defined the legal profession.

Author

Dr Aaron Timoshanko is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Law and Justice at the University of Southern Queensland.

Aaron’s main research foci lie in corporate law, accountability, and regulatory theory. Aaron’s PhD thesis was conferred in 2018 by Monash University and was awarded the 2018 Mollie Holman Medal for the best thesis for the Faculty of Law.

Prior to undertaking postgraduate study, Aaron worked in-house and as a solicitor in private practice.

Dr Julie Copley, University of Southern Queensland

Introduction

This blog post argues for greater thoughtfulness about the legal norms of housing when housing security initiatives are being developed by Australian governments.[1]

The contention is that use of new/old thinking about housing — and the security, peace and dignity housing ought to afford each person — would clarify disparities in terminology and understandings of the governments’ role under our Australian legal system, ensuring a sharper and shared focus on the urgent problem of housing insecurity.

Analysis and synthesis of research findings set out below is about, first, terminology and, second, what the law requires.

Budget Speech 2024: A focus on ‘more homes’

In the 2024 Budget Speech, the Federal Treasurer said:

We’re easing the cost of living — and we’re building more homes for Australians.

In the 5 years from this July, we aim to build 1.2 million of them.[2]

A budget day media release from the Federal Housing Minister stated:

The Albanese Labor Government is turbocharging the construction of new homes across the country – building more homes for home buyers, more homes for renters and more homes for Australians in every part of the country. …

The 2024-25 Budget includes $6.2 billion in new investment to build more homes more quickly, bringing the Albanese Government’s new housing initiatives to $32 billion.[3]

The explicit Budget objectives, and the terms used by the Treasurer and Minister, can be compared with language about housing insecurity and homelessness used by Australian people in a human rights context, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ reporting of Census data.

First, a 2014 Australian Human Rights Consultation found that a key human rights concern of Australian people is ‘access to affordable housing and homelessness’.[4]

Second, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reports that, at the time of the last Census in 2021:

122,494 people were estimated to be experiencing homelessness on Census night in 2021… 23.0% of all people experiencing homelessness were aged from 12 to 24 years… Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people [represented] one in five (20.4%) people experiencing homelessness in Australia.[5]

Mismatch in ‘homelessness’ terminology

On the face of it, there is a mismatch in terminology.

On the one hand, the Government announces initiatives for ‘more homes’. On the other, the AHRC identified concerns in response to questions put to people about their human rights (especially ‘property rights’) and reported that people said ‘[t]he right to property provides security, and enables opportunities for economic and social development’.[6]

The ABS data, moreover, is gathered from responses to questions framed according to the ABS statistical definition of ‘homelessness’. The definition is:

when a person does not have suitable accommodation alternatives, they are considered as experiencing homelessness if their current living arrangement: is in a dwelling that is inadequate; has no tenure, or if their initial tenure is short and not extendable, or; does not allow them to have control of, and access to space for social relations.[7]

Empirical and legal definitions of ‘homelessness’

One reason for a mismatch is because a distinction must be drawn between definitions for empirical and legal purposes.

As Christopher Essert (University of Toronto, Faculty of Law) explains, there can be clear differences between a person’s empirical situation and their legal status. Instances of homelessness can be ‘empirically indistinguishable from instances of non-homelessness’; for example, when ‘someone sleeps outside or sleeps in a large room with lots of other people on a mat on the floor and yet does not count [themselves] as homeless’.[8]

Public sector and third sector bodies researching and developing policy rely on an empirical approach as ‘to know who ought to be targeted by such policies, we need to know who counts as homeless.’[9] For these purposes, the ABS statistical definition is adopted commonly in Australia.

However, when law is to be made — and it is important to note here that Budget appropriations are authorised by legislation (law made by parliaments) — a legal rather than an empirical definition is preferable.

Jeremy Waldron, for example, refers to a person who has ‘no place governed by a private property rule where he is allowed to be whenever he chooses, no place governed by a private property rule from which he may or may not at any time be excluded as a result of someone else’s say-so’.[10]

Samuel Tyrer suggests use of the term ‘rooflessness’, affording a wide definition extending to a situation where a person has no physical shelter nor any experience of ‘home’.[11]

Conceptual mismatch: Housing as a commodity vs a human right

A second reason for a mismatch is due to different conceptualisations of the problem and the effectiveness of solutions.

Jessie Hohmann (UTS Faculty of Law) contends Australian governments focus on housing as a commodity rather than on securing, protecting and promoting a human right to housing.[12]

The latter is, in fact, the approach adopted for the ABS statistical definition. It is ‘constructed from a conceptual framework centred around: adequacy of the dwelling; security of tenure in the dwelling, and; control of, and access to space for social relations’.

Ahead of the 2026 Census also, the statistical definition will be reviewed, as recommended by a parliamentary committee, to examine ‘the circumstances in which people living in severely crowded dwellings and boarding houses should be categorised as homeless.’[13]

Note, in this context, the incongruity of the ‘commodity’ in the 2024 Budget: ‘homes’, not houses. The incongruity arises because, as Tyrer explains, ‘the home experience’ comprises three dimensions: ‘(a) the feeling of security; (b) the expression of self-identity; and (c) relationships and family.’

Australia’s international law obligations

The likely reason for a conceptual mismatch, Hohmann argues, is a lack of awareness of what law requires. A set of requirements is stated clearly, however, in an international law obligation Australia adopted nearly half a century ago.

In 1975, the Australian Commonwealth ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights without reservations, and the ICESCR entered into force in Australia in March 1976. Under Art 11(1) of the ICESCR:

the States Parties … recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate … housing …

Towards a progressive approach to housing security

So, acting consistently with the ICESCR obligation, Australian governments would not announce spending for ‘more homes’. Australian governments would work progressively to ensure all policies and legislation secure, protect and promote a person’s right to adequate housing.

Nor would the right be given a narrow interpretation: the expert oversight body for the ICESCR (the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights) states that the right demands that each person ‘live somewhere in security, peace and dignity.’[14]

Author

Julie Copley is a Lecturer in Law in the School of Law and Justice at the University of Southern Queensland. She is based at the Ipswich campus.

Julie has significant public and private sector experience working with legislation and in legislative policy. Since 2016, she has been researching and teaching in the School of Law and Justice at UniSQ. In her research and her teaching, Julie encourages others to appreciate legislation as an authoritative source of law and the legislative process as a dignified mode of governance.

[1] Jeremy Waldron, Thoughtfulness and the Rule of Law (Harvard University Press, 2023); Julie Copley, ‘A Right to Adequate Housing: Translating “Political” Rhetoric into Legislation’ (2023) 31 Australian Property Law Journal 71.

[2] Treasury Portfolio, ‘Budget Speech 2024–25, Delivered on 14 May 2024 on the second reading of the Appropriation Bill (No. 1) 2024–25’, available at: <https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/jim-chalmers-2022/speeches/budget-speech-2024-25>

[3] Ministers for the Department of Social Services, The Hon Julie Collins MP, Minister for Housing, Minister for Homelessness, ‘Homes for Australia Plan: Delivering more homes for Australians – 14 May 2024’.

[4] Australian Human Rights Commission, Rights and Responsibilities: Consultation Report (2015) 39, available at <https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/rights-and-freedoms/publications/rights-responsibilities-consultation-report>.

[5] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Estimating Homelessness: Census Latest release (Released 22/03/2023)’, available at: < https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating-homelessness-census/latest-release>.

[6] AHRC (n iv).

[7] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘4922.0 – Information Paper – A Statistical Definition of Homelessness, 2012’, available at: < https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/4922.0>.

[8] Christopher Essert, ‘Homelessness as a Legal Phenomenon’ in N Graham, M Davies and L Godden (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Property, Law and Society (Taylor & Francis, 2022) 137–139.

[9] ibid, 138.

[10] Jeremy Waldron, Liberal Rights: Collected Papers 1981–1991 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[11] Samuel Tyrer, ‘Home in Australia: Meaning, Values and Law?’ (2020) 43 University of New South Wales Law Journal 340, 341.

[12] Jessie Hohmann, ‘A Right to Housing for the Victorian “Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities”?: Assessing Potential Models under the “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights”; the “European” Social Charter; and the “South African Constitution”’ (2022) 48 Monash University Law Review 132, 159.

[13] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Estimating Homelessness: Census methodology’, available at: <https://www.abs.gov.au/methodologies/estimating-homelessness-census-methodology/2021>.

[14] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), General Comment No 4, 6th sess, UN Doc E/1992/23 (13 December 1991) annex III, [7].

Jonathan Crowe, University of Southern Queensland and Gianni Ribeiro, University of Southern Queensland

Earlier this month, Queensland became the latest state to pass affirmative consent laws. This means consent is understood as ongoing communication for the purposes of rape and sexual assault offences.

Under affirmative consent, agreement to each sexual act must be actively communicated. That is, each person must say or do something to indicate consent and check the other is willing to proceed.

It’s common for victims of sexual assault to freeze or try to avoid further injury, rather than fighting back. The new laws make it clear these reactions are not consent.

But it’s not just Queensland that has such laws. Where else are they in place, and how are they working in practice?

What do Queensland’s laws do?

The new Queensland laws define consent as “free and voluntary agreement”. They clarify that a person does not consent where they do not “say or do anything to communicate consent”.

The laws also limit the mistake of fact excuse for rape and sexual assault. This excuse allows defendants to argue they honestly and reasonably — but mistakenly — believed the other person consented to sex.

The excuse has been heavily criticised for allowing defendants to rely on irrelevant factors, such as the other person’s clothing or failure to fight back, as the basis for alleged mistakes about consent.

However, the new laws say a belief in sexual consent is not reasonable unless the person took active steps to check their partner was consenting. This is consistent with an affirmative consent model.

Where else has similar laws?

Four out of the six Australian states and one of the two territories have now enacted affirmative consent laws. Tasmania was the first state to adopt an affirmative consent model in 2004.

The Queensland laws follow on the heels of recent legal changes in NSW, the ACT and Victoria. NSW and the ACT legislated affirmative consent in 2021, while Victoria did the same in 2022.

Western Australia and South Australia, meanwhile, are currently reviewing sexual consent laws and may well follow suit.

The national trend is clearly towards an affirmative consent standard. Some scholars have argued this could pave the way to aligning sexual consent laws across the nation — although significant challenges remain.

Critics of affirmative consent laws have suggested they could criminalise “spontaneous marital sex”. However, this ignores the social and legal context within which the laws operate.

There is no evidence of the laws being applied in this way.

Vital for debunking rape myths

Affirmative consent laws can only be effective and fair if people understand what they mean in practice.

However, public attitudes are not always consistent with an affirmative consent model. A NSW government study found 14% of young men “didn’t agree that you must seek consent every time you engage in sexual activity”.

Societal attitudes are clouded by persistent myths about consent and sexual violence. For example, people may think that someone who was drunk or did not fight back cannot be a victim of rape.

Rape myths are not limited to the general public. They influence judges, lawyers, police and jurors as well. Recent research has found rape myths in supreme court judgments and jurors’ perceptions of evidence in rape trials.

It is easy to assume that once affirmative consent laws are passed, they will be fully effective in the courts. However, years after affirmative consent was adopted in Tasmania, courts were still applying outdated legal principles.

Raising public awareness

For affirmative consent laws to serve their purpose, everyone — including judges, lawyers, jurors, police and the public — needs a clear understanding of what affirmative consent means.

Public awareness campaigns can help to clarify that consent is an active, ongoing process that cannot be inferred from silence or lack of resistance.

NSW’s Make No Doubt campaign was launched the week prior to its new consent laws taking effect, but a similar campaign has yet to be announced in Queensland.

The Queensland Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce heard from victim-survivors, support services, lawyers, police and the broader community about the need for improved public education on consent.

Understanding consent in isolation is not enough. Comprehensive education on respectful relationships is vital to fostering a culture where affirmative consent becomes the norm.

The effectiveness of affirmative consent laws also depends on how they are applied by police, lawyers and judges. If police don’t give effect to the laws, then most sexual assaults will never reach prosecutors — let alone the courtroom.

Comprehensive training for these professionals is essential to ensure affirmative consent is implemented across the criminal justice system.

Since Australia’s affirmative consent laws are so new, there is limited evidence (beyond Tasmania) of exactly how they will work in practice. It will be important to build this evidence base to ensure the laws are functioning as intended.

Government action is essential

Online resources, such as Rape and Sexual Assault Research and Advocacy’s sexual consent toolkit, can help people learn about affirmative consent. However, these resources only reach a small part of the community.

To raise wider awareness of affirmative consent and to overcome persistent rape myths, large-scale efforts are needed.

Governments across Australia should invest in the success of affirmative consent laws through further public awareness campaigns, as well as training and education for criminal justice professionals and the public.

Otherwise, affirmative consent laws could turn out to be just words on paper.

Authors

Jonathan Crowe is Head of School and Dean of the School of Law and Justice at the University of Southern Queensland.

Professor Crowe is Director of Research at Rape and Sexual Assault Research and Advocacy.

Gianni Ribeiro is a Lecturer in Criminology in the School of Law and Justice at the University of Southern Queensland. She is based at the Ipswich campus.

Dr Ribeiro receives funding from the Australian Institute of Criminology.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Introduction

Jury deliberation is considered a cornerstone of fair trial proceedings. However, a newly published study in Frontiers in Psychology in January 2024, which I co-authored, delves into a crucial issue: the potential for jurors to misremember key evidence from the trial and introduce misinformation during deliberations.

Background

The problem of memory distortion is well-documented in the context of eyewitness testimony, where misinformation can compromise the reliability of witness accounts (see Loftus, 2005, for a review). Discussion among eyewitnesses is a known source of memory distortion and can result in memory conformity, where each eyewitnesses’ account of the event starts to resemble other eyewitnesses’ accounts. As a result, discussion between eyewitnesses is discouraged in efforts to preserve memory integrity. However, in jury deliberations, it is assumed that discussions will enhance jurors’ memory of the key details relating to the case, leading to more accurate verdicts (Pritchard and Keenan, 1999, 2002; Hirst and Stone, 2017; Jay et al, 2019).

Before our research, only one study had explored whether misinformation introduced in jury deliberations affected juror memory and decision-making (Thorley et al, 2020). They found that the more misinformation mock jurors accepted (ie, misremembered it as evidence from the trial), the more likely they were to reach a guilty verdict.

Results

Our research builds on Thorley and colleagues’ (2020) work by also exploring the effect of pro-defence misinformation and whether judicial instructions warning jurors about misinformation may mitigate its influence in a sexual assault trial.

In our first study, we found that participants were more likely to misremember pro-prosecution misinformation as having been presented as evidence during the trial compared to pro-defence misinformation. However, misinformation did not impact ultimate decision-making in the case, which may be attributed to most participants (87.6%) leaning towards a guilty verdict prior to deliberation.

Therefore, in our second study, we used a more ambiguous case that resulted in a more even split of verdicts pre-deliberation (66.7% guilty). Here, we found that participants who received pro-defence misinformation were more likely to misattribute the misinformation as coming from the trial than participants who received pro-prosecution misinformation. Further, pro-defence misinformation led to a decrease in ratings of defendant guilt and complainant credibility, and an increase in the strength of the defendant’s case. However, the judicial instruction about misinformation exposure had no effect.

Conclusion

Together, the findings from our two studies suggest that misinformation introduced during jury deliberations may indeed distort memory of trial evidence and impact decision-making. Although there is popular support for judicial instructions as a legal safeguard, there is mixed evidence for their effectiveness and our research found that there was no effect of warning jurors about potential misinformation prior to deliberation. These findings call for a deeper exploration of strategies to maintain the integrity of juror deliberations and ensure the fairness of trial verdicts.

The article is open access, so you can read and download it for free here.

Author

Gianni Ribeiro is a Lecturer in Criminology in the School of Law and Justice at the University of Southern Queensland. She is based at the Ipswich campus.

Prior to joining the School of Law and Justice in 2023, Gianni obtained her PhD in applied cognitive and social psychology from The University of Queensland in 2020 with no corrections. She was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the School of Psychology at the University of Queensland working in collaboration with Queensland Police Service.

By A/Pr Ciprian Radavoi

With the next pandemic likely not far ahead, the debate over the suitability of a broad, general vaccination mandate (‘GVM’) goes on. Proponents insist on utilitarian arguments related to the common good, while opponents rely on autonomy and individual freedom of choice.

In an article forthcoming in World Medical and Health Policy, I propose a novel argument in favour of GVM: vaccination should be mandatory because, in the fear-dominated climate of a pandemic, it becomes mandatory anyway — just not in a de jure, parliament-sanctioned form. As former Australian Prime Minister Morrison has put it, the government will make vaccination “as mandatory as you can make it”. That is, left to its own devices, executive power, from governments to the local administration and even corporations, will tend to impose on the non-vaccinated restrictions of such harshness that vaccination becomes de facto mandatory.

Public health policy is supposed to follow the so-called ‘ladder of intervention’, moving gradually from the least to the most restrictive measures in order to attain a certain objective. In pandemics, the objective is reaching herd immunity by having a high enough proportion of vaccinated. At the top of the ladder there is forcible vaccination, obviously prohibited in democratic countries. Next down the ladder are statutory mandates backed with fines, like the one imposed in Austria and a few other countries. Next down, there is a grey area where there is no official general mandate to vaccinate but, to persuade the population to do the right thing, all sort of prohibitions are imposed on the unvaccinated.

As making life difficult to the unvaccinated was at the heart of pro-vaccination policies in the COVID-19 pandemic, they were banned from pubs, churches, shops, etc. An element of reasonable choice remained for most of these: the pubgoer had the option to drink at home, the churchgoer could dispense with the priest’s service for a while and speak to the Divinity directly, the shopper could shop online or ask a friend to shop for them, and so on.

But when the place you are banned from is the workplace, we are no longer talking about a real choice. ‘No jab, no job’ is not the same as ‘no jab, no pub’. Work is much more than the right to do a job and get a salary in return. As individuals we obtain an income allowing for a decent life (food, clothing, housing, medicines), but also dignity, self-esteem, and social recognition. A person who is denied the right to work is exposed to the risk of poverty, mental harm, and even suicide.

Given the fundamental importance of the right to work, and the longer effect of restrictions on this than on other rights in pandemics, “vaccination or joblessness” is not a reasonable choice the worker is presented with. Without choice, there is coercion. With coercion, there is a mandate. A de facto mandate, more precisely – one imposed by the executive (public or private) power in the absence of statutes stipulating general mandatory vaccination. And this creates three serious problems from a democracy and rule of law perspective:

- First, banning the unvaccinated from the workplace was done in the COVID-19 pandemic — despite the fundamental importance of the right to work to the human being — without any genuine examination of the elements of balancing (necessity, proportionality) required whenever a right is limited by the authorities.

- Second, numerous employers sacked the unvaccinated even in jurisdictions where this was not supported or required by public regulation. Corporate overreach, in the form of banning the unvaccinated from the workplace despite the lack of laws requiring this radical measure, is especially concerning given the increased concentration of unchecked power in private hands, in the contemporary globalised world.

- And third, in a more general perspective, claiming that something mandatory is not mandatory is a case of legal hypocrisy. Legal hypocrisy obscures the harm inflicted on persons and communities, thus silencing the victims. It also erodes trust in the rule of law and in democratic institutions: how can the citizen believe in a system that publicly honours the fundamental liberal value of personal autonomy, while at the same time dismisses it in practice?

In the charged climate of a pandemic, overly zealous action by public and private executive power, including dismissal of the unvaccinated, seems inevitable, with the noxious effects enumerated above. It is better to fence this otherwise laudable zeal by simply making general vaccination de jure mandatory, with all the benefits deriving from this official status in terms of setting the proper balance between the rights and interests at stake. Intrusions into the right to work would be inevitable, but dismissal as a coercion tool would not be used. Indeed, in a parliamentary debate conducted without pressure before the next pandemic hits, dismissal for vaccination refusal would likely not pass the tests of necessity (since the pandemic is temporary, a temporary suspension would suffice) and proportionality (uncertain benefits in exchange for a very severe blow to a fundamental right).

Ciprian Radavoi is an Associate Professor in the School of Law and Justice at the University of Southern Queensland.

Ciprian is a lawyer and former diplomat, currently teaching and undertaking legal research in Australia (international law, tort law, sports law, human rights and social justice).

Recent Comments