By Nicole C McWha, JD graduand at the University of Southern Queensland

My Child’s Story: From Discovery to Treatment

In 2014, my then 13-year old child came to me and told me they did not identify with the gender assigned to them at birth. I had never heard the word ‘transgender’ before, and my first thought was that my child had jumped on the latest bandwagon. My child assured me they had never identified as being female and that it had become progressively distressing to feel like a boy while being known to everyone else as a girl.

When you witness your child suffer with the painful blisters from wearing a chest binder, cry when they cannot go swimming with their friends, and become increasingly depressed, it is easy to support the decision.

My child gave me several online links and I went down the wormhole. I signed up for a Gender Studies course and volunteered for several events put on by the Edmonton Pride Centre for youth. At 15, my child wanted to begin hormone replacement therapy (HRT), also known in Australia as gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT).

The Legal Framework: How ‘Mature Minor’ Rights Work

Treatment was accessible with a medical diagnosis of ‘transgenderism’, or gender dysphoria. We were only required to obtain authorisation signed by their endocrinologist stating my child was fit to be deemed a mature minor and capable of making their own informed medical decisions. This authorisation granted access to ‘top surgery’ when my child was 16.

I risk judgment by parents who may not agree with my decision to support what my child wanted. When you witness your child suffer with the painful blisters from wearing a chest binder, cry when they cannot go swimming with their friends, and become increasingly depressed, it is easy to support the decision to undergo a procedure that is, in a way, reversible.

It wasn’t relevant that their father did not approve; indeed, it wasn’t relevant whether I did either. The ‘mature minor principle’ which developed in Canada means there is a rebuttable presumption that a child over the age of 16 has capacity to understand the implications of their own medical decisions (Alberta College of Social Workers, 2015). Unless there is doubt of the child’s capacity, a court will not intervene. Children under 16 will ‘have the right to demonstrate mature medical decisional capacity’: AC v Manitoba (Director of Child and Family Services) [2009] 2 SCR 181, 184. Such a determination is made by a medical practitioner (College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta, 2015, 7). This is a strict application of Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority [1986] AC 112 where Lord Scarman stated that ‘parental right[s] to determine whether or not their minor child below the age of 16 will have medical treatment terminates if and when the child achieves a sufficient understanding and intelligence to enable him or her to understand fully what is proposed’ (1986, 189[H]–190[A]).

The Policy Reversal: 2024’s Dramatic Changes

Policy Evolution Timeline: 2013–24

Although the common law respecting minors in both Canada and Australia developed from the Gillick decision in the United Kingdom, both countries differed in its application.

In Australia, there has been a slow transition from mandatory court approval for gender-affirming care. Re Jamie [2013] FamCAFC 110 opened the door for children’s access to hormone blockers without the need for court approval and Re Kelvin [2017] FamCAFC 258 eliminated the need for court approval for GAHT — so long as there existed the mutual consent of the child, their medical practitioners, and their parents.

Alberta’s Ban: From Access to Prohibition

On 31 January 2024, the United Conservative Party of Alberta announced changes to legislation that would undermine Canada’s mature minor doctrine. In less than a year, amendments to the Health Professions Act, RSA 2000, c H-7 prohibited children’s access to ‘hormone therapy’ for the treatment of gender dysphoria (which includes hormone blockers and GAHT).

News sources repeated the government’s assurances that a Ministerial Order would be made excluding children over 16 from the ban, so long as there was consent from parents and a medical team. Thus far, there have been no Ministerial Orders made. As of today, all children under age 18 remain prohibited from any hormone therapy whatsoever for the treatment of gender dysphoria (Health Professions Act, ss 1.91–1.93).

Queensland Follows Suit

Within two months of Alberta’s legislative changes, the Liberal National Party of Queensland similarly announced a new Health Service Directive prohibiting treatment of gender dysphoria in children by putting a halt on the distribution of hormone blockers and GAHT. Equally similarly, Queensland’s ban also completely undermines what has been established at common law.

Jurisdiction Comparison: Alberta vs Queensland

🇨🇦 Alberta, Canada

🇦🇺 Queensland, Australia

The Cass Review Connection

Interestingly, the changes in Alberta and Queensland come within a year of the Cass Review (a controversial and disputed report on the alleged effects of gender-affirming care given to children in the United Kingdom) (see McNamara et al, 2024 Grijseels, 2024; Horton, 2024; Noone et al, 2024; compare Cheung et al, 2024, McDeavitt, Cohn and Levine, 2025).

Legal Challenges and Constitutional Questions

Directly after the amendments to the Health Professions Act were implemented in December 2024, a civil suit was filed by advocacy groups on behalf of five children, seeking interim injunctions on the grounds that Alberta’s ban on gender-affirming care is unconstitutional, contrary to the province’s Bill of Rights, and ‘takes important health care decisions out of the hands of gender diverse young people, their parents and guardians, and places these decisions in the hands of the state’ regardless of the ‘due care and skill and … professional judgment’ exhibited by their health care practitioners acting in consideration for the child’s best interests (Egale Canada, 2024).

In Queensland, it seems the government has preempted the possibility of legal action because it has expressly permitted infringement of a child’s best interests and ‘right of access to health services’ (Queensland Government, 2025). While the legislative changes in Alberta do not expressly permit such infringement, it is possible a favourable court decision could be circumvented by the Notwithstanding Clause, which prevents court interference (Ashley, 2024, p 89).

What This Means for Families Today

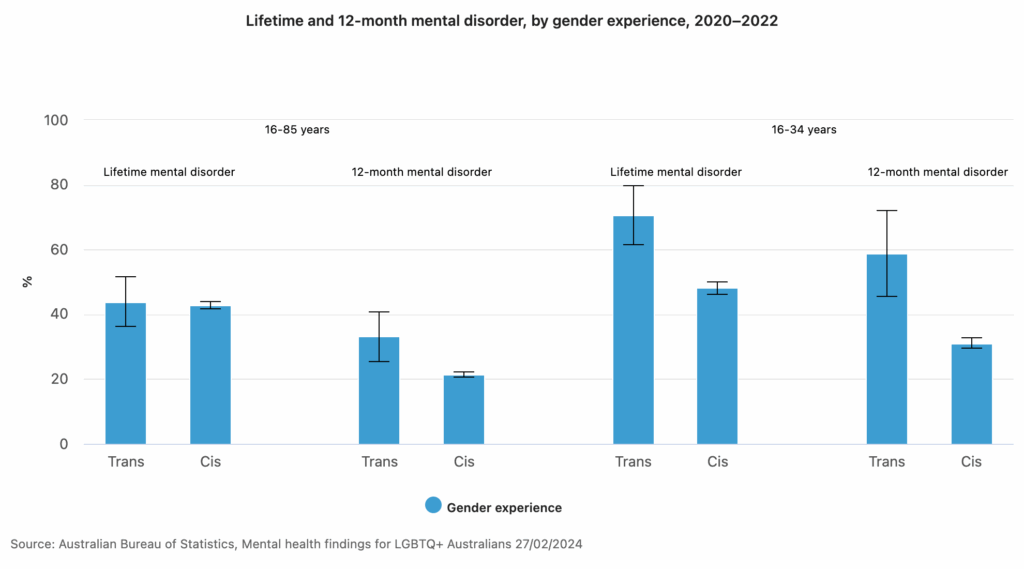

Transgender children are already prone to overwhelming depression often accompanied by self-harming tendencies and suicidal ideation where gender-affirming care is unavailable or impossible (Coleman et al, 2022; Grant et al, 2025).

The fallout from Alberta’s and Queensland’s bans on gender-affirming care will no doubt include an increase in the number of children seeking care outside of these jurisdictions, and an uproar made by health care practitioners who feel helpless to assist a group of very vulnerable youngsters. There has already been a petition started to remove state interference with access to gender-affirming healthcare.

Looking Forward: Hope and Advocacy

We can only surmise why today’s conservative governments would have any interest in disregarding decades of case law which would permit children to be at peace with themselves. As I watch with hopeful anticipation the changes will soon be reversed, I am relieved that my child was able to receive the care they needed a decade ago.

About the Author

Nicole C McWha is a Canadian resident and has just recently become a UniSQ graduand having completed her Juris Doctor degree. She has also been a family law legal assistant for nearly 15 years. Passionate about both the justice and political systems, Nicole has always been an advocate for reform where there still exists a failure to ensure basic human rights. She is excited to begin the next chapter of her legal career. Away from the law, Nicole enjoys spending time with her two young adult children and with all their fur-babies.

Leave a Reply