By Dr Nicky Jones, University of Southern Queensland

Editor’s note

When Australian soccer star Sam Kerr called a London police officer ‘f***ing stupid and white’ in January 2023, her words led to an international legal debate about racial language. The February 2025 verdict finding her not guilty of racially aggravated harassment raises key questions: When does mentioning someone’s race constitute racial hatred? Does calling someone ‘white’ carry the same weight as other racial terms?

In a previous post, Associate Professor Andrew Hemming examined the implications of Sam Kerr’s acquittal on free speech legislation in Australia. In this post, Dr Nicky Jones examines the Kerr case through the lens of Australian law. Her examination reveals how courts interpret racial language when directed at historically dominant versus marginalised groups.

Introduction: Racially-charged insults

On 11 February 2025, global media reported the outcome of a five-day trial in the Kingston Crown Court in London. The court had to decide whether Australian soccer player Sam Kerr had made comments that racially harassed a Metropolitan Police officer on 30 January 2023.

Kerr made these comments at the police station when she grew impatient with the police officer who appeared to doubt her version of events. She thereupon called him ‘f***ing stupid and white’. The officer showed no concern about these insults in his first statement shortly after the incident.

However, 11 months later, the officer provided a second statement. This came after the Crown Prosecution Service (‘CPS’) had declined to charge Kerr. In this later statement, he said that Kerr’s comments made him feel ‘shocked, upset and humiliated’.

One year after the incident, the CPS charged Kerr with a racially aggravated offence of intentional harassment under s 4A(1) of the UK’s Public Order Act 1986 and s 31(1)(b) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

Under these sections, a person is guilty of an offence if the person intends to cause another person harassment, alarm or distress by using threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, or disorderly behaviour, that causes the other person harassment, alarm or distress. It is a further offence if the public order offence is racially aggravated.

Australian anti-discrimination provisions use similar language to prohibit offensive behaviour based on racial hatred. Section 18C(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) prohibits an act that was done in public because of another person’s race or colour or national or ethnic origin if the act was reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate the other person. Similar State and Territory laws prohibit racial vilification, and Queensland and some other States impose civil and criminal sanctions on racial vilification.

This post focuses on the racial aspect of Kerr’s comments. It explains how Australian laws would treat similar racial insults. The post will not describe the events that led to Kerr’s trial or the trial itself as these have been well-documented elsewhere. The post draws its information from news reports and video footage filmed by police body cameras that recorded Kerr’s interactions with the police.

These events raise challenging questions about racial insults, hatred and vilification and to whom and how these wrongs apply for the purposes of pursuing legal protections.

Calling a person ‘white’

Is it racially insulting to call someone ‘white’? In important legal respects, calling someone ‘white’ is not a racial insult in an Australian or UK context.

Australian anti-discrimination law requires courts to consider ‘all the circumstances’ of an act or insult. This includes context and (in this case) the historical and cultural situation of white people and whiteness in society.

Legal tests for racial insults

Section 18C(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) sets out two important elements:

- The impact of an offensive act, assessed objectively; and

- Causation or the reasons behind the offensive act.

Courts assess impact from the perspective of a hypothetical ordinary, reasonable member of the racial group targeted by the act. Would an ordinary, reasonable member of that racial group have been offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by the act?

The words ‘offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate’ carry their ordinary meaning. In Creek v Cairns Post Pty Ltd, Justice Kiefel noted that these are ‘profound and serious effects, not to be likened to mere slights.'[1] Justice French also considered these terms in Bropho v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission,[2] as did Justice Bromberg in Eatock v Bolt.[3]

Establishing that the act produced one of these responses from an ordinary, reasonable member of the targeted racial group is sufficient. When determining impact, the context (‘all the circumstances’) in which the act took place is significant.[4]

Case spotlight: McLeod v Power

The facts in McLeod v Power closely resemble the Kerr incident.[5] This case involved a verbal altercation between an Aboriginal woman and a white correctional officer. The woman swore repeatedly at the officer, calling him names such as a ‘white piece of ****’.

Federal Magistrate Brown noted that in the Australian context, calling someone ‘white’ is not of itself a term of abuse. Undoubtedly the woman swore at the officer because she wished to cause offence and to protest at what she saw as the arbitrary and unreasonable nature of his decision to refuse her entry to the prison so that she could visit her partner.

However, in the context of the matter, a reasonable correctional services officer with a pale skin would not have been offended, humiliated or intimidated by the addition of the words ‘white’ or ‘whites’ to the respondent’s verbal abuse. The words were not of themselves offensive words or terms of racial vilification. White people are the dominant people historically and culturally in Australia. They are not in any sense an oppressed group whose political and civil rights are under threat.

… in the Australian context, calling someone ‘white’ is not of itself a term of abuse… white people are the dominant people historically and culturally in Australia and are not in any sense an oppressed group whose political and civil rights are under threat.

Brown FM dismissed the officer’s complaint. Although a reasonable prison officer might find the words offensive generally, they would not have been offended by the racial implication specifically. It did not constitute racial hatred or vilification.[6]

Conclusions

Kerr clearly intended to insult the London police officer when she called him ‘stupid and white’. She admitted this under cross-examination.

News reports repeated the police constable’s second statement that the words made him feel ‘upset’, ‘belittled’ and ‘shocked’. He said ‘they went too far and I took great offence to them’. Even Judge Peter Lodder KC noted after the trial that ‘[Kerr’s] own behaviour contributed significantly to the bringing of this allegation.’

Nevertheless, the UK jury quickly found Kerr not guilty of racially aggravated harassment.

Australian courts would likely reach the same conclusion under racial hatred provisions. Adapting Brown FM’s detailed reasoning in McLeod v Power, Kerr used insulting comments ‘to express her frustration at what she perceived as being a power imbalance between herself and [the officer]’ in a ‘stark and confrontational manner’.[7]

The words offended, but they did not exemplify the racial hatred that the Racial Discrimination Act aims to prohibit. As Brown FM stated:[8]

it is drawing a long bow to use the Racial Discrimination Act in this way and was certainly not the primary purpose of the legislature in enacting legislation of this kind.

References

[1] (2001) 112 FCR 352, [16].

[2] (2004) 135 FCR 105, [67]–[69].

[3] (2011) 197 FCR 261, 323–5.

[4] See Drummond J’s comments on this point in Hagan v Trustees of the Toowoomba Sports Ground Trust [2000] FCA 1615, [15], [18]–[31]. See also Creek v Cairns Post Pty Ltd (2001) 112 FCR 352, [12]-[16].

[5] (2003) 173 FLR 31.

[6] Ibid [59]-[60], [69].

[7] Ibid [62].

[8] Ibid.

Image attribution: Spotlight icons created by mavadee – Flaticon

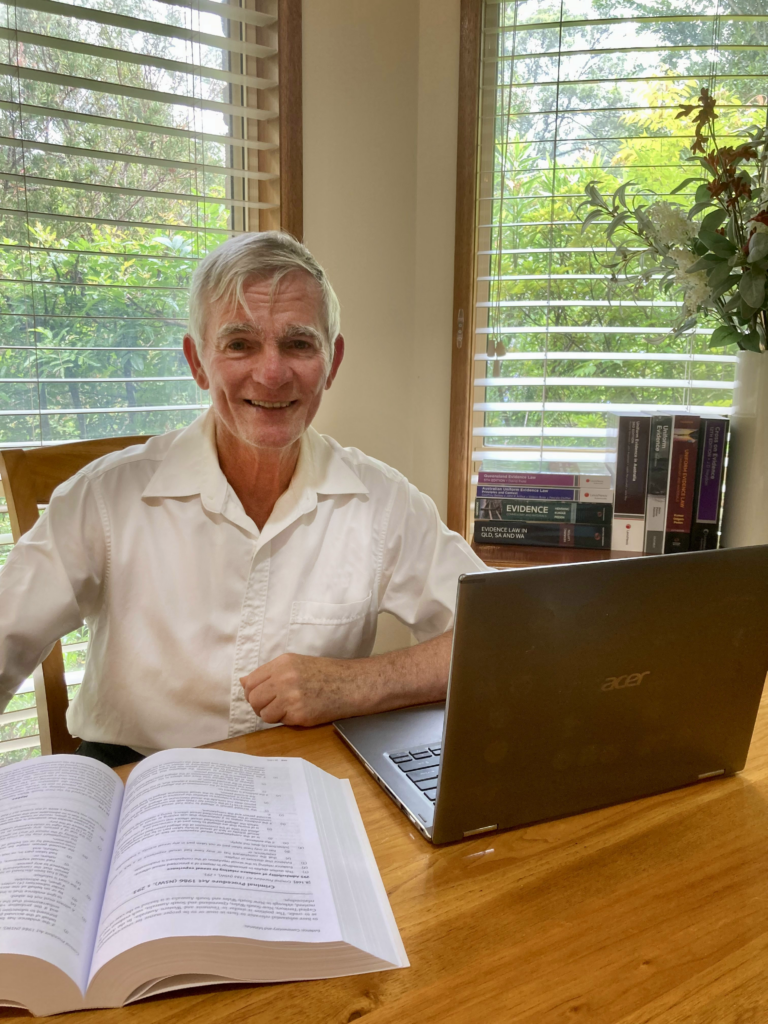

About the author

Dr Nicky Jones teaches public international law and human rights and anti-discrimination law at the University of Southern Queensland. In 2023, Nicky’s book An Annotated Guide to the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) (written with Peter Billings) was published by LexisNexis. Recently, she has been appointed to the Queensland government’s Human Rights Advisory Panel. While studying law, Nicky interned at the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, where she worked with Brian Burdekin AO, former Australian human rights commissioner, in the National Institutions team. After graduating, Nicky worked as a judge’s associate for the Hon Justice Margaret McMurdo AC FAAL (then President of the Court of Appeal in Queensland). Nicky worked briefly in private practice and Crown Law before returning to academia. She is admitted to practice in the Supreme Court of Queensland and the Federal and High Courts of Australia.

Recent Comments