Author: Annabel Luxford (USQ JD student)

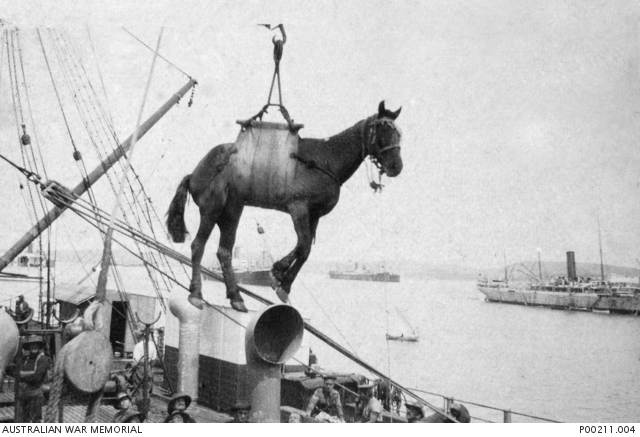

The catalyst for change is often not recognised in the moment it occurs. Something minor and seemingly unremarkable can lead to things we would never expect. In a famous scene in the movie Jurassic Park, Jeff Goldblum’s character Dr Ian Malcolm says, ‘a butterfly can flap its wings in Peking, and in Central Park you get rain instead of sunshine’.[1] He was discussing chaos theory which looks at the unpredictability in complex systems.[2] In a similar way, a horse falling off a ferry in medieval England brought about changes in the legal system that had far reaching effects into the future and across the world.

The Humber Ferry Case[3] from 1348 is an important English legal case. It set in motion a series of changes that have shaped the way we understand obligations and liability under modern contract[4] and torts[5] law. Had it not been for that ill-fated day where the horse was lost to the River Humber, our law may have developed quite differently.

A ferry, a mare overboard and a bold plaintiff

John de Bukton paid Nicholas Tounesende of Hessle, a ferryman at a crossing on the River Humber in Yorkshire, to carry his mare over the river. The plaintiff, Bukton, claimed that the ferryman, Tounesende, overloaded the boat with horses and, as a result, his horse was lost overboard and died.

Like many changes that are set in motion, timing is everything. It was at the same time that Bukton lost his mare to the river, that the King’s Bench, which still occasionally travelled from Westminster, had arrived in York in 1348. Looking for a remedy to his loss, Bukton boldly decided to bypass the local courts for an answer. He brought a Bill of Complaint before the King’s Bench. What was so bold about his decision? Well firstly he did not have a writ, but rather a Bill of Complaint. Secondly, at that point in time, the King’s Bench did not hear cases like that of the plaintiff. It was the Court of Common Pleas that would usually hear matters between private citizens. Bukton did not have an action for trespass in the royal courts on the facts of his case.

Up until the mid-thirteenth century, trespass was only an option to recover damages where there were allegations that someone had committed a wrong that was a breach of the King’s peace, and where there had been a vi et armis (force of arms).[6] As A W B Simpson writes, ‘[t]he function of this grave allegation in the fourteenth century, and earlier, had been to justify the intervention of the royal courts, by showing that the King had a special interest in the wrong, for at this period there was a feeling — one could almost call it a theory — that, in general, case involving private wrongs should be determined in the local courts.’[7]

It would have seemed unlikely in 1348 that the King’s Bench would hear the plaintiff’s case. There was no writ, no allegation of force and no breach of the peace. Where was the royal interest? Donahue interestingly points out the royal interest can perhaps be found in the fact that the River Humber, where the incident occurred, was part of the King’s Highway.[8] Whether or not this was the reason for allowing the case, Bukton was granted permission to bring his complaint before the King’s Bench.

How the matter played out in the royal court

In the King’s Bench, the defendant’s attorney, Richmond, argued that a trespass action was the wrong action to bring and that a writ of covenant should have been brought. However, as there was no sealed document (deed) between the ferryman and the plaintiff for the carriage of the horse over the river, a writ of covenant would not have been available to Bukton.

It was a legal requirement at the time that to sue for breach of covenant there had to be a deed. The writ of covenant was a limited remedy. It failed to protect everyday verbal agreements between parties[9] such as the one between the defendant and the plaintiff. In arguing that a trespass action had been inappropriately brought by the plaintiff, Richmond stated that there was no allegation that the defendant had killed the horse and as such there was no tort or wrongdoing (the basis for trespass).[10] However, a Justice of the King’s Bench, Baukwell, responded to such an assertion that the wrong or trespass was in fact committed when the ferryman overloaded the boat so the mare perished.[11]

The King’s Bench held that an action, despite the absence of the use of force, could be brought for trespass — the claim was against the harm done to the horse, and not merely the failure to transport it across the river. As such, no documentary evidence of a covenant was needed. The Court found in favour of the plaintiff and ordered the defendant to pay 40 shillings.[12]

Undertakings, negligence and the path to assumpsit

The legal ramifications of the court’s decision in the Humber Ferry Case was significant. They had for the first reported time allowed an action of trespass to apply to the damage and loss caused by a badly performed agreement.[13] There are two important aspects here for the evolution of the law. Firstly, the harm done was not directly caused (with force of arms as trespass called for) but was merely negligent. By allowing accidental harm to be remediable in a trespass action, the way was paved for action on the case for negligence, and from that the modern law of tort.

Secondly, there was no longer the requirement for a breach of the peace. A defendant could now be liable for damage if the defendant undertook (assumpsit) to do a job for a plaintiff but did it ‘so negligently or unskilfully as to cause harm to the plaintiff’s person or property’.[14] Stoljar has cleverly described the new action of assumpsit as, ‘slipping into the unoccupied middle ground of trespass and covenant’.[15] It seems, even back in medieval England, that the law was fluid and it developed organically to fit the needs of the time.

From assumpsit to the modern law of contract and torts

By the fifteenth century, writs started including assumpsit super se indicating that someone had undertaken to do something rather than breaching the peace. In the years that followed the Humber Ferry Case, the new approach to assumpsit was applied firstly to the ill performance of an undertaking (misfeasance)[16] and later to the non-performance (nonfeasance) of undertakings.[17] Thus the basis of the modern law of contract was born.

By the end of the seventeenth century, negligence was emerging as the basis for an independent wrong in itself, based on the defendant’s failure to take reasonable care.[18] Before this, actions for negligence were limited to the negligent performance or non-performance of an undertaking or discrete wrongs.[19] Plunkett notes that the recognition of the concept of ‘duty of care’ filled a gap for plaintiffs: ‘[c]laims that would fail in contract could now be converted to claims that would succeed in tort. ‘[20]

The judiciary’s development and articulation of the obligations and duties owed under contract and tort has been extensive since the King’s Bench travelled to York in 1348. It is fair to say, however, that the foundation of contract and torts law can be found in the Humber Ferry Case and the centuries that followed.

Looking back to look forward

Looking back in time to the Humber Ferry Case does more than shed light on the origins of the law of contracts and torts. It reminds us how English law has and continues to evolve organically and sometimes unexpectedly. The catalyst for important changes can sometimes be a seemingly unremarkable event like a horse perishing on a ferry. What might seem like a small event at the time can set in motion changes that have drastic effects on legal doctrines that are felt far into the future. Taking the time to explore and understand legal history helps us to have an informed understanding of what is happening today. It helps us become better decision makers and agents of change both in the legal profession and the community at large.

Reference List

- John Baker and SF Milsom, Sources of English Legal History: Private Law to 1750 (Oxford University Press, 2010)

- Charles Donahue Jr, ‘The Modern Law of Both Tort and Contract: Fourteenth Century Beginnings?’ (2017) 40(1) Manitoba Law Journal 9

- Albert Kirafly, ‘The Humber Ferryman and Action on the Case’ (1953) 11(3) Cambridge Law Journal 421

- James C Plunkett, ‘The Historical Foundations of The Duty Of Care’ (2015) 41(3) Monash University Law Review 716

- M J Sechler, ‘Supply versus Demand for Efficient Legal Rules: Evidence from Early English Contract Law and the Rise of Assumpsit’ (2011) 73 University of Pittsburgh Law Review 170

- A W B Simpson, A History of the Common Law of Contract: The Rise of the Action of Assumpsit (Clarendon Press, 1975).

- S J Stoljar, A History of Contract At Common Law (ANU Press, 1975)

- Robert Bishop, Chaos, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Web page) <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/chaos/>

[1] Jurassic Park (Amblin Entertainment, 1993).

[2] Robert Bishop, Chaos, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Web page) <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/chaos/>.

[3] Bukton v Tounesende (1348) (‘Humber Ferry Case’) JH Baker and SFC Milsom, Sources of English Legal History: Private Law to 1750 (Butterworths, 1987).

[4] ‘A contract is an agreement or promise between two or more parties that is legally enforceable’: Oxford Australian Law Dictionary (3rd ed, 2017) ‘contract’.

[5] ‘Torts is the law of civil wrongs not arising out of a contractual relationship and includes claims such as negligence’: Oxford Australian Law Dictionary (3rd ed, 2017) ‘torts law’.

[6] A W B Simpson, A History of the Common Law of Contract: The Rise of the Action of Assumpsit (Clarendon Press, 1975) 202.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Charles Donahue Jr, ‘The Modern Law of Both Tort and Contract: Fourteenth Century Beginnings?’ (2017) 40(1) Manitoba Law Journal 9, 15.

[9] MJ Sechler, ‘Supply versus Demand for Efficient Legal Rules: Evidence from Early English Contract Law and the Rise of Assumpsit’ (2011) 73 University of Pittsburgh Law Review 161, 170.

[10] Simpson (n 6) 211.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Albert Kiralfy, ‘The Humber Ferryman and Action on the Case’ (1953) 11(3) Cambridge Law Journal 421, 422.

[13] SJ Stoljar, A History of Contract At Common Law (ANU Press, 1975) 29.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] The Farrier’s Case (1373), cited in Donahue (n 8) 33s; The Surgeon’s Case cited in Donahue (n 8) 38.

[17] Somerton v Colls (1433) in JH Baker and SFC Milsom, Sources of English Legal History: Private Law to 1750 (Oxford University Press, 2010) 427; Shipton v Dogge [No 2] (1422) in JH Baker and SFC Milsom, Sources of English Legal History: Private Law to 1750 (Oxford University Press, 2010) 434.

[18] James C Plunkett, ‘The Historical Foundations of the Duty Of Care’ (2015) 41(3) Monash University Law Review 716, 718.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid 719.

Recent Comments